2024-2025 Ghalya Saadawi's seminar: Counter, Revolution, Film - Part II

The seminar is conceived and offered by Ghalya Saadawi

The seminar from Confluence to Confluence

Seminar participants second year: Alva Roselius, Clara Rudin Smith , Sam Mountford, Tereza Darmovzalová

Seminar participants first year : Zhuang Leng, Stellar Meris, Rana Kelleci, Ilja Schamle, Olfa Arfaoui, Tara White, Sophie Dandanell Refsgaard

Counter, Revolution, Film, Part II

One year into the media streamed genocide of Palestinians by the ethno-fascist state of Israel and its Western supporters, and now a new wave of deranged Israeli pummeling of Lebanon erasing entire villages and neighbourhoods (and spreading to Syria and Iran for their Gulf-endorsed New Mid East), in its bid to be rid of the last armed front of resistance against normalization with Israel, the long arc of the War on Terror and the capitalist and imperial wars we have always been in, come to roost.

We are well into the Western liberal order’s thrashing of the remnants of international and humanitarian law – designed by those early and neo-liberals, and by the supporters of WWII’s never again. And well into the ruling order’s masks falling off through the in-broad-daylight arms supplying, doxing, silencing, terrorizing with accusations of antisemitism for support of the Palestinian cause, through propaganda wars, and lest we forget, bombs on Yemen. All to keep the expansion and circulation of capital going and going. Where do we even begin, or end, to show more images, or speak language? What did we see before that helps us see what we see and cannot see, or unsee today? Yes, Adorno was right. Something does happen to language; language itself is at stake, complicit, in need as a Symbolic arrangement of rearrangement, reclamation, and destructive re-invention.

We continue to live in counterrevolutionary times. Modernity’s long arc produced different sites for counterrevolution understood as many things from colonial repressive states apparatuses, to puppet regimes quashing communism, to preemptive terror wars. It did so as far back as commerce’s “rounding of the cape” into a later phase of industrial accumulation. For this to happen you needed the Cold War’s US led military coups and communist purges across Latin American, Africa, South Asia and the Arab region; the rise of nationalist fascisms across Europe (now and then), followed by debt and devastation in the name of rebuilding; all arching with class and race wars in the imperial core from McCarthyism, eviscerating left trade unionism to an intensified, carceral state. In fact liberal democracy itself after its bourgeois revolutions, has become a leading force of counterrevolution in the covering over of its founding violence, the fear it holds that those who came to suffer at its hands would double down on it with more violence, forged as they were for Fanon, by that very violence. Capitalism itself continues to perfect its counterrevolutionary formations.

The range of these counterrevolutionary historiesare connected via an accumulative, propertied bloodline. Alberto Toscano after W. E. B. Du Bois calls it ‘the counter-revolution of property’ in considering fascism as contiguous with capitalism and colonialism. One that works hard to obscure its historical founding, even as it makes clear its intentions. These bloodlines are connected through various military, legal, and mediatic techniques that we are long familiar with: criminalization, incarceration, forced disappearance, death-squads, espionage, and media propaganda. The counterrevolution also accomplishes its aims through using peaceand human rights.

So after the potted history: Film was the scene of political praxis and critique since the invention of the camera. Political and economic struggles took multiple cultural, hear also aesthetic modalities, including those of the moving image: new waves of fiction, newsreel, documentary. What Kodwo Eshun and Ros Gray also call ‘the militant image’, placed film in the context of Third World and non-aligned colonial liberation struggles, as well as in the context of class struggle and revolutionary insurgency. Issues of form and content framed the poles of realism and modernism in Marxist thought, and bulleted film, documentary and scholarship by crystallizing around various points of contention: montage, sound and text, archival footage, narrative. There are evidently vast splits in considering the path of filming the revolution and counterrevolution, and whether the apparatus of the camera and its attendant machinations were understood as a weapon, a text, a medium of representation, a formal language, or an ideological hindrance.

Last year we covered Part I of this seminar. Fred Moten has this phrase, ”the wars we have always been in”. The seminar’s first session was on “That peaceful violence that the world is steeped in,” as Fanon would call it in The Wretched of the Earth. We read his exploration of the dialectical relation between the colonised and the coloniser; the struggle of freedom through violence; the role and psychic state of what he called the national bourgeois, meaning the ruling class and its national rulers between metropole and colony; and his critique of the politics of neutralism. We considered Gilles Pontecorvo film, “La Bataille D’Algiers” from 1969 through the lens of our reading of Fanon, and we read Alberto Toscano’s commentary on the legacy of French intellectual history inflected through its responses to and engagements with the Algerian war of Independence and the so-called subject of decolonization.

From Algiers, our second session led us to the Palestinian revolution of the 60s and 70s via Jean Luc Godard's and Anne Marie Mieville's “Içi et Ailleurs” (1976). As part of the film collective the Dziga Vertov Group's methodological injunction to make political films, politically, Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin and Mieville filmed footage of Palestinian fidayeen in 1969-1970 in Jordan, only to make and edit “Içi et Ailleurs” in the context of Paris several years later, once many of those fighters had been killed in Black September. Bringing in the class contradictions and political struggle in France over communism at the time, as well as the central social role played by images themselves into the Palestinian revolution against Zionism, the film finds formal codes to contend with political struggle, foregrounding how cinematic images are constructed, and what absent images inform the ones we do see. We read critical texts on the film, on Godard’s work, and on the struggle for Palestine in the 60s and 70s.

Session three forced us to go back to some basics in regards to what we mean by revolution and totality insofar as the legacy so-called western and cultural Marxism was concerned. We read Marx and Engels, and Eric Hobsbawm and Perry Anderson’s commentaries on Western Marxism. And to engage with the conception of totality under capitalism, we read Toscano and Jeff Kinkle’s Cartographies of the Absolute to chart the trajectory of “cognitive mapping” via cinematic and aesthetic engagement to represent unfathomability and scale in capitalist operations. We watched Alexander Kluge “Marx and Eisenstein” (2008) and Sydney Lumet “Network” (1972).

Finally, we landed on fascism and its devices with the help of film and psychoanalysis. We read Theodor Adorno on fascist devices of the interwar and world war years, and we read Toscano on the late fascism of our times. We began to outline interwar fascism and current day iterations as Toscano bids us to, with an emphasis on what Marxist analysis may need to understand in the of fascism if it is not to make similar analytical mistakes to its predecessors. Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator” (1940) Roger Corman’s “The Intruder” (1962) held the cinematic scope of some of the analyses laid out in our readings.

In Part II we will continue to read about what counterrevolution demonstrate. And what film theory, in each case, helps elucidate. We will watch films to explore terrains of an always brutal counterrevolution – be it internally, or via imperial wars. This force of ruling class and imperial order, if you will, produces an aesthetic, too, as it produces the aesthetic fervour of that which it wishes to extinguish. As we roam time and geography, we can learn something about letting the imagepuncture and remake the image of now.

The seminar proposes four sessions (open to change and discussion):

1. The counterrevolution against communism as it later connects to The Black Panther Party and as far as today’s carceral state (e.g. Orlando de Guzman; Riotsville USA dir. Sierra Petengill; The Manchurian Candidate dir. John Frankenheimer);

2. The Paris Commune (e.g. La Commune dir. Peter Watkins);

3. The Brixton riots, and race and class war in the UK (e.g. Handsworth Song dir. Black Audio Film Collective; The Battle of Orgreave dir. Mike Figgis/Jeremy Deller);

4. The War on Terror, surveillance and counterterrorism (e.g. Citizen Four dir. Laura Poitras; War at a Distance dir. Harun Farocki; American Sniper dir. Eastwood or Last Flag Flying dir. Linklater, etc.).

Additional:

5. The subprime mortgage (financial) crash, bank bailouts, austerity (e.g. The Big Short, dir. Adam MacKay, Costa-Gavras, Melanie Gilligan).

6. The Indonesian Killings

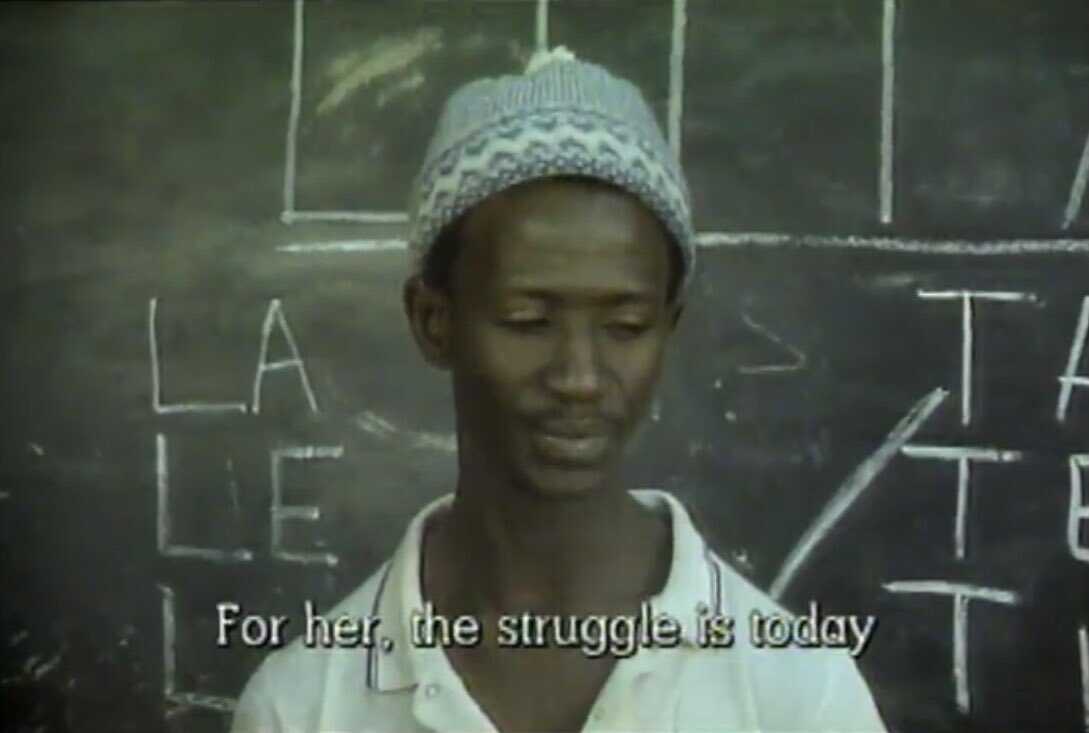

7. Guniea Bissau’s war of independence (Mortu Nega, dir Flora Gomes).

Extended reading list – weekly readings upcoming:

Aaron J. Leonard and Connor A. Gallagher (2015). Heavy Radicals: The FBI's Secret War on America's Maoists. London: Zero Books.

Alter, Nora (1996) The Political Im/perceptible in the Essay Film: Farocki’s Images of the World and Inscriptions of War. New German Critique 68 (special issue on literature): 165–192.

Barrett, Michele. “Max Raphael in the Question of Aesthetics.” New Left Review 1/161 January-February 1987: 79-97.

Baumann, Stefanie (2021). "Images of the Real. Introductory Notes 1." Cinema Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image 12: 8-21.

Bevins, Vincent (2020). The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. New York: Public Affairs.

Davis, Angela (2016). If They Come in the Morning…: Voices of Resistance. London: Verso.

Eshun, Kodwo, and Ros Gray, eds (2011).”The Militant Image: A Ciné‐Geography. Editors’ Introduction.” Third Text, 25, no. 1: 1-12. ++ Essays from the issue.

Fanon, Frantz (1963). The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Constance Farrington. London: Penguin.

Harvey, Sylvia (1982). “Whose Brecht? Memories for the Eighties.” Screen 23, no. 1: 45-59.

James, CLR (1946). “They Showed the Way to Labor Emancipation: On Karl Marx and the 75th Anniversary of the Paris Commune,” Labor Action Newspaper of the Workers Party of the United States (March 18, 1946). Last accessed November 12, 2023 https://libcom.org/article/karl-marx-and-paris-commune-clr-james.

de Laurot, Edouard (2011). “Composing as the Praxis of Revolution: The Third World and the USA.” Third Text 25, no. 1: 67-91.

Marcuse, Herbert (1972). Counterrevolution and Revolt. Boston: Beacon Books.

Marx, Karl (1848). “The Bourgeoise and the Counter Revolution.” Neue Rheinische Zeitung 169. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/12/15.htm

Marx, Karl (1871). “The Paris Commune.” In The Civil War in France. Last accessed November 3, 2023 https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/ch05.htm

Meister, Robert (2012). After Evil: The Politics of Human Rights. New York: Columbia University Press.

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. (1990). “Documentary Is/Not a Name.” October 52: 76-98.

Rabinowitz, Paula (2004). They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary. London: Verso.

Rodowick, D. N. (1995). The Crisis of Political Modernism: Criticism and Ideology in Contemporary Film Criticism. Oakland: University of California Press.

Ross, Kristin (2016). Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. London and New York: Verso.

Watkins, Peter. (2004). “Notes on the Media Crisis,” http://www.ocec.eu/cinemacomparativecinema/index.php/en/11-materiales-web/387-notes-on-the-media-crisis

Whyte, Jessica (2019). The Morals of the Market: Human Rights and the Rise of Neoliberalism. London and New York: Verso.

Extended film ideas for screenings and homework:

Solanas and Getino, The Hour of the Furnaces (1973)

Stanley Kubrik, Doctor Strangleove (1964)

Thom Andersen, Red Hollywood (1996)

Stewart Bird, Rene Lichtman and Peter Gessner, Finally We Got The News: The League of Revolutionary Black Workers (1970)

Heiny Srour, The Hour of Liberation (1974)

Ivens, Marker, Klein, Resnais, Varda, Godard, Lelouch, Loin du Vietnam (1967)

Joshua Oppenheimer, The Act of Killing (2011)

Godard, La Chinoise (1967)

Stefanie Black, Life and Debt (2001)

Sarah Gomez, One Way or Another (1974)

Wes Hondo, West Indies: The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty (1979)

Dziga Vertov, Man with a Movie Camera (1925)

Sergei Eisenstein, Battleship Potemkin (1925) or Ten Days that Shook the World (1928)

Harun Farocki Images of the World and Inscriptions of War (1989)

Barbet Schroeder, Terror’s Advocate (2008)

Alexander Kluge Marx and Eisenstein (2008)

Flora Gomes Mortu Nega (1988)

Trinh T. Minh-ha (1983) Reassemblage: From the Firelight to the Screen

.