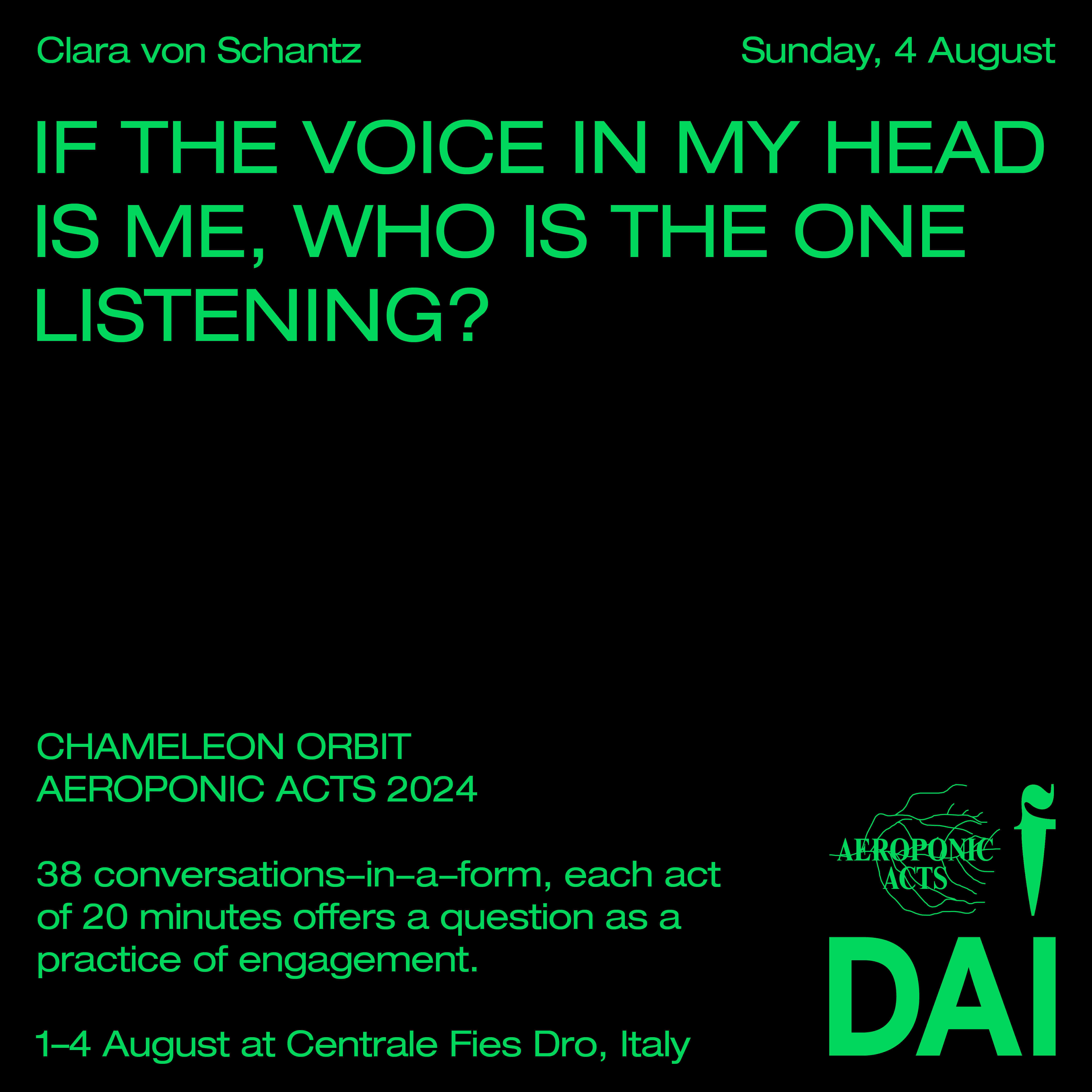

Clara von Schantz ~ Once Upon A Fight

On a rainy and windy day, two identical characters take the stage. Amidst their everyday arguments, they swap roles; rehearsing what it is to be, exploring the boundaries of selfhood. In the never-ending pursuit of becoming the sole winner, they steer away aimlessly, beginning anew as soon as it ends. Holding a script, a third figure emerges, narrating and guiding the characters’ actions. Somewhere between self-creation and arm wrestling, mundanity of everyday life takes hold.

By blurring the lines between the interior and exterior, the vanished and the haunted, the living and the dead, the singular and the double, identity may split—leaving behind a scattered and interconnected unit that never, fully, came to be.