Riots: Slow Cancellation of the Future ~ exhibition curated by Natasha Ginwala ~ from 26 Jan till 1 April at ifa-Galerie

Opening: Thursday, 25 January 2018, 7 pm

ifa-Galerie Berlin

Linienstraße 139/140

10115 Berlin

Curated by Natasha Ginwala

Assistant Curator: Krisztina Hunya

With John Akomfrah, Chto Delat, Dilip Gaonkar, Gauri Gill, Louis Henderson, Satch Hoyt, Jitish Kallat, Karrabing Film Collective, Glenn Ligon, Daniel Joseph Martinez, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, SAHMAT, Chandraguptha Thenuwara and Ala Younis

“The learning process is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot.”

– Audre Lorde

The riot is an extra-ordinary setting that has played a pivotal role in the permanent confrontation between dissent and power over centuries. The deeper crises of capitalism, racial violence, and communal tensions have convulsed us into “an age of riots”.[i] As master fictions of the sovereign nation-state implode and hegemonic silencing of the dispossessed only serves to reveal the cracks in governability, the exhibition Riots: Slow Cancellation of the Future brings together artistic works and research positions from across the world in an endeavour to “sense” and chronicle recent riots and uprisings – evoking a phenomenology of the multitude.[ii]

Social theorist Dilip Gaonkar asks, “How might one account for the persistence of rioting and the rioting crowds of people within the evolving trajectory of capitalist time and terrain? In my judgment, our time and terrain is caught in an inextricable paradox: coveting crowds and fearing riots.”[iv] Within the exhibition he presents a video collage assembled from feature films, newsreels, and documentaries that operate as a propositional timeline grasping “the politics of disorder”, including riots, crowds, mass funerals, and street politics. In correspondence stands Jitish Kallat’s installation Anger at the Speed of Fright(2010) depicting a turbulent crowd in miniature form. The rioters are frozen in positions of stone pelting, mass beating, and escaping police brutality – attackers and victims caught in blind fury. Kallat ensures that this circuit of human violence is seen as an aerial scene, so we may reflect on the explosive dimension and dystopias acting in a global metropolis.

The Learning Flags (2011) by the collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?) – a working group of artists, critics, philosophers, and writers – provoke an engagement with underlying dynamics between radical learning and collective action. How may these flags become a source for an improvised pedagogy of street activism and perform as a theatrical structure for sustained study? This work lies at the threshold between the gallery and the street, examining agential modes in cultural labour and thinking around the utility of art.

In the posters, publications, music concerts, and exhibitions organised by the Delhi-based SAHMAT collective (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust) since 1989, we find aesthetic strategies that have struggled against the rise of communal forces while defending artistic freedom, secular traditions, and plurality in history-telling. This display highlights some of the key interventions realised by SAHMAT after the demolition of the Babri Masjid (Babur’s Mosque, 1992), the Bombay riots (1992–93), and the 2002 Gujarat riots.

Gauri Gill’s long term project 1984 (2014) assembles a range of voices, including artists, writers, poets, and film-makers with survivors’ testimonies recalling the anti-Sikh genocide that occurred in New Delhi in 1984. Gill invites a dialogue between her photographs first published in print media and resilient modes of response that form a notebook and bibliography, countering the void left by necropower.

For the past decade Chandraguptha Thenuwara has marked the memory and changing significance of the 1983 Black July riots in Sri Lanka with an annual exhibition. Through drawing and installation work, he plots the monstrosity of mob violence, disappeared bodies, state control of urban space through self-initiated concepts such as “Barrelism”, and rapid gentrification in the aftermath of civil war.

Developing from iconic film evidence of bread riots in Egypt in 1977 and radio reports in Jordan following the entry of refugees from Iraq in 1990, Ala Younis has created a “stereoscopic” study concerned with the rousing of riots and civic disorder through rumours, bureaucratic leaks, and manipulation of public opinion. Her project assesses the images streamed through mobile cameras and televised mass demonstrations in Egypt, including the way social media feeds perform a kind of algorithmic terror by constructing new pathways for bigotry.

In the Karrabing Film Collective’s commissioned installation They Been Jealous,(2018), riots in indigenous Australia correlate with the accumulative possession of traditional lands by the settler state. Karrabing members consider the character of contemporary jealousy, while also remapping indigenous terrains through both social and mythic modes that structure forms of difference and obligation.

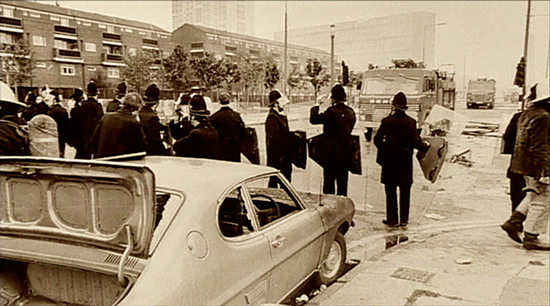

John Akomfrah’s seminal film Riot (1999) traces the riots in Liverpool during July 1981 in a climate of economic recession under Thatcher’s regime. Akomfrah captures this turning point in Britain’s struggle towards multicultural democracy through interviews revealing the ghettoisation and racial abuse in Toxteth that escalated with stop-and-search policing tactics following the “sus” laws. Louis Henderson’s latest film Evidence of Things Unseen but Heard (2017) draws a relation between technologies of state surveillance against black communities in Bristol, the rise of sound system culture, and the exceptional character of “Bristol sound”. Shot around the St Pauls neighbourhood, while reflecting on Bristol’s history, which heavily rests on plantation labour and slavery, Henderson stitches a sonic archaeology through archival photographs of the St Pauls carnival and the direct aftermath of the riots of 1980.

Glenn Ligon investigates the problems of language and representation when recounting histories of African-American identity. In his silkscreen print, Untitled (Condition Report for Black Rage) (2015), the book cover of Black Rage (1968) becomes his focal point in reading white anxieties around the black body and anger. By highlighting clinical markings such as in a conservation report, the smudges and repairs perform an incisive commentary on America’s broken social fabric. Satch Hoyt’s sculptures Riot (2014) and Bula Matari (2013) appropriate sources of punishment, such as the bullwhip, police batons, and the water hose, to address black experience and racial violence. While the sonic memory of whip-cracking remains tied to records of slavery, blows of a baton resonate as a Victorian-era measure of riot control that are still in “action” everywhere.

What does it mean to restrain bodies in defiance, keeping in view accounts of twentieth-century race riots? In her work Fuel to the Fire (2016), Natascha Sadr Haghighian responds to the carceral state – legacies of imperial violence and racial segregation with the steady build up of police militarisation. Haghighian has chosen the newspaper as a key medium, building dialogue with community action groups and social justice activists to reflect on the structural injustice that led to the so-called Stockholm riots. Haghighian and her collaborators chronicle a murder that took place over five years ago in Stockholm’s Northern suburb of Husby, when a local resident named Lenine Relvas-Martins was shot in his own apartment by Piketen police (SWAT police).

The Watts rebellion and the founding of the SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) police in 1960s Los Angeles are further mediated in the personal experience and sculptural work of Daniel Joseph Martinez. He revisits the iconic photograph of Black Panther revolutionaries Bobby Seale and Huey Newton at the party headquarters in California, treating their continued presence in Carrara marble as guardians who are watchkeeping towards the futurity of Black Power. Martinez leads us to reckon with how images carry testimony and remain “haunting refrains” in a fissured present.

Riots expose the anti-disciplinary core of a society – its rebellious spirit but also the traumatic fallout. Evidence lurks everywhere as traces inhabiting social relations and becoming the scars of a city, yet we cannot ever fully grasp this condition. In drawing from the reading of “the slow cancellation of the future” by Franco “Bifo” Berardi and Mark Fisher,[v] this exhibition wrestles with lost futures while investigating micropolitics of the crowd and the many languages of uprising that refuse the “loophole of retreat”.[vi]

[i] Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (London and New York: Verso, 2016).

[ii] Dilip Gaonkar, “After the Fictions: Notes Towards a Phenomenology of the Multitude”, e-flux Journal, 58 (October 2014).

[iii] Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power (London: Phoenix, 2000), pp. 20–21.

[iv] Gaonkar, “After the Fictions” (see note 2).

[v] Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (UK: Zero Books, 2014).

[vi] Borrowed from African-American writer and reformer Harriet Ann Jacobs, in her autobiographical novel Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).