Zoé Couppé ~ À la vie à la mort A voice and nothing more

Today this stage is my stage, this is my stage, my dance floor. The Present enters the stage, discussing with the Past and the Future.

What is happening backstage? Where is it? Would you like to know? maybe not. What, and who enters the stages? Who is present? and who is missing? Who is missing on the stage today?

There is always more to hear in the folds, and we have to strain our ears. From speech to song, from whisper to cry, the performance A la vie à la mort, A voice and nothing more explores where the voice appears and disappears.

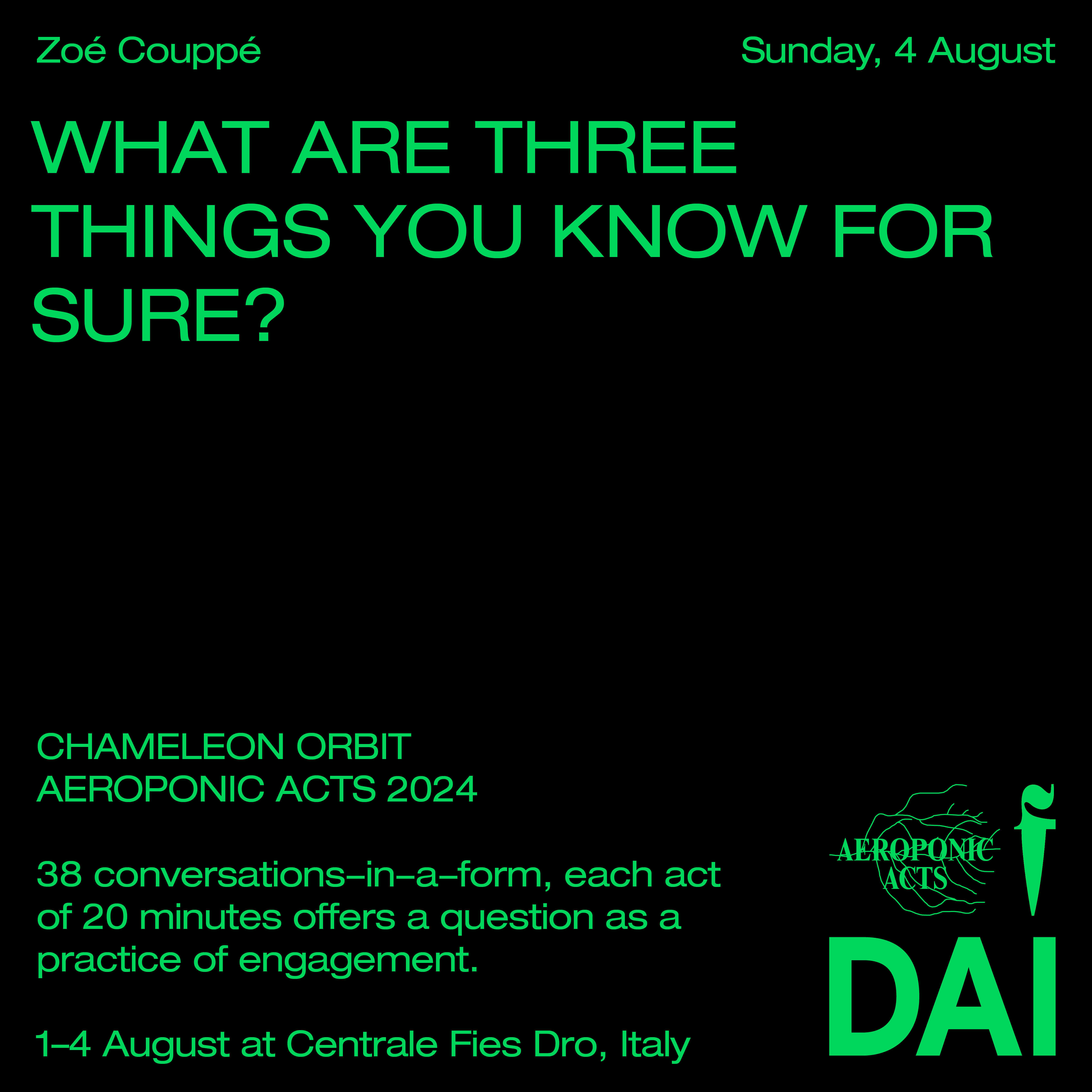

AEROPONIC ACTS 2024 ~ Chameleon Orbit

About Zoé Couppé