Tomer Fruchter ~ KORBANOT – An act of faith

A performer enters the room carrying a clumsy luggage piece; swiftly unpacks the entire suitcase contents on the concrete floor, disclosing an assortment of personal offerings: drawings from across the century, what is seemed to be a peculiar stool, freshly printed zines and a blunt knife.

The Hebrew language places both the words Art (OMANUT) and Faith (EMUNA) in a shared field of meaning, suggesting a worn-down yet overlooked proposition: the artist’s role is that of an everlasting believer making sacrifices in the face of an unknown outcome.

While most European cultural worlds have thrown art out the window as it proved insufficient in mobilizing social change, Israeli artists of today are holding onto the artistic act and its faculties in a collaborative quest for spiritual survival. Retreating into an ancient collective imagination as a project of breaking through one of the most horrifying and deadly loops of our times.

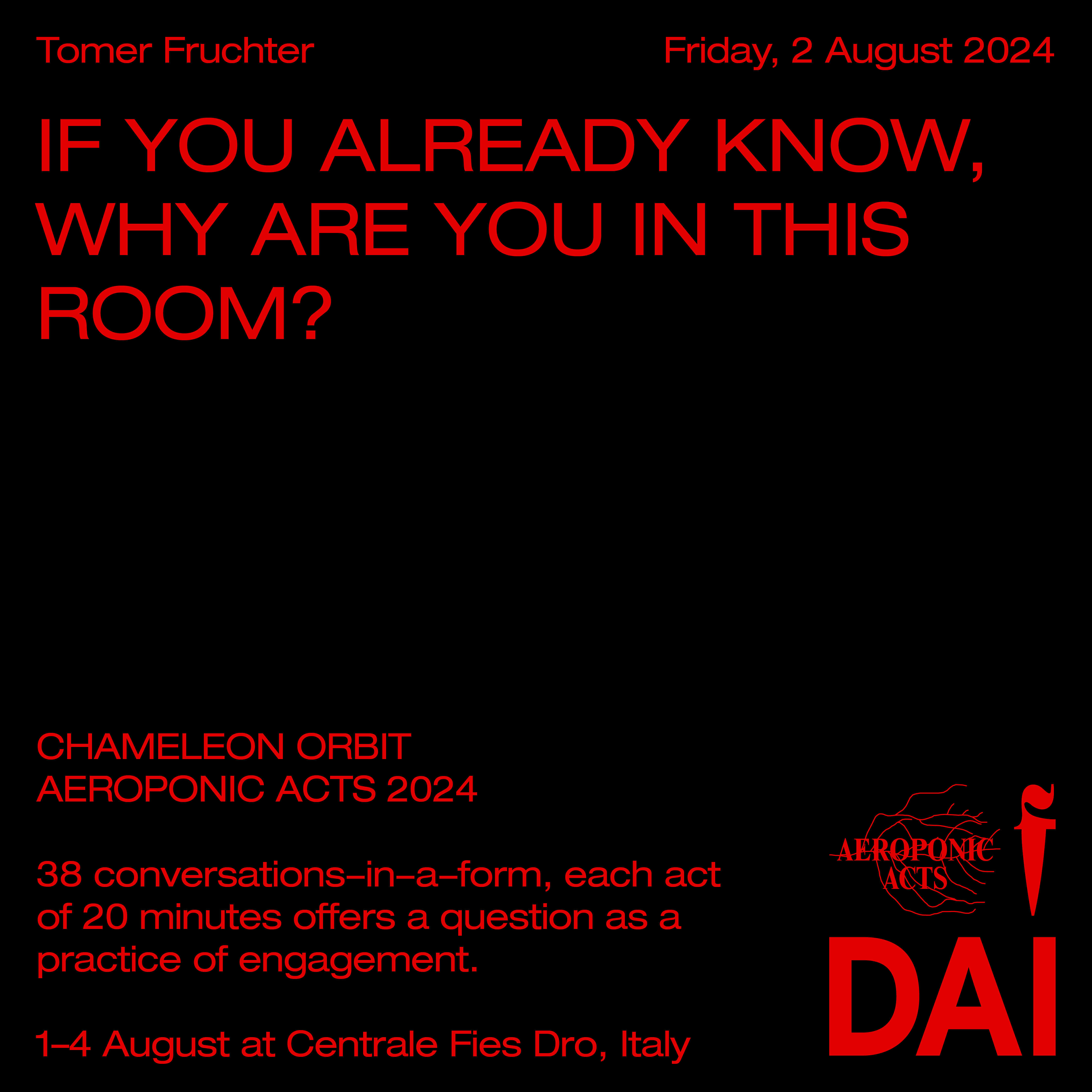

AEROPONIC ACTS 2024 ~ Chameleon Orbit

About: Tomer Fruchter