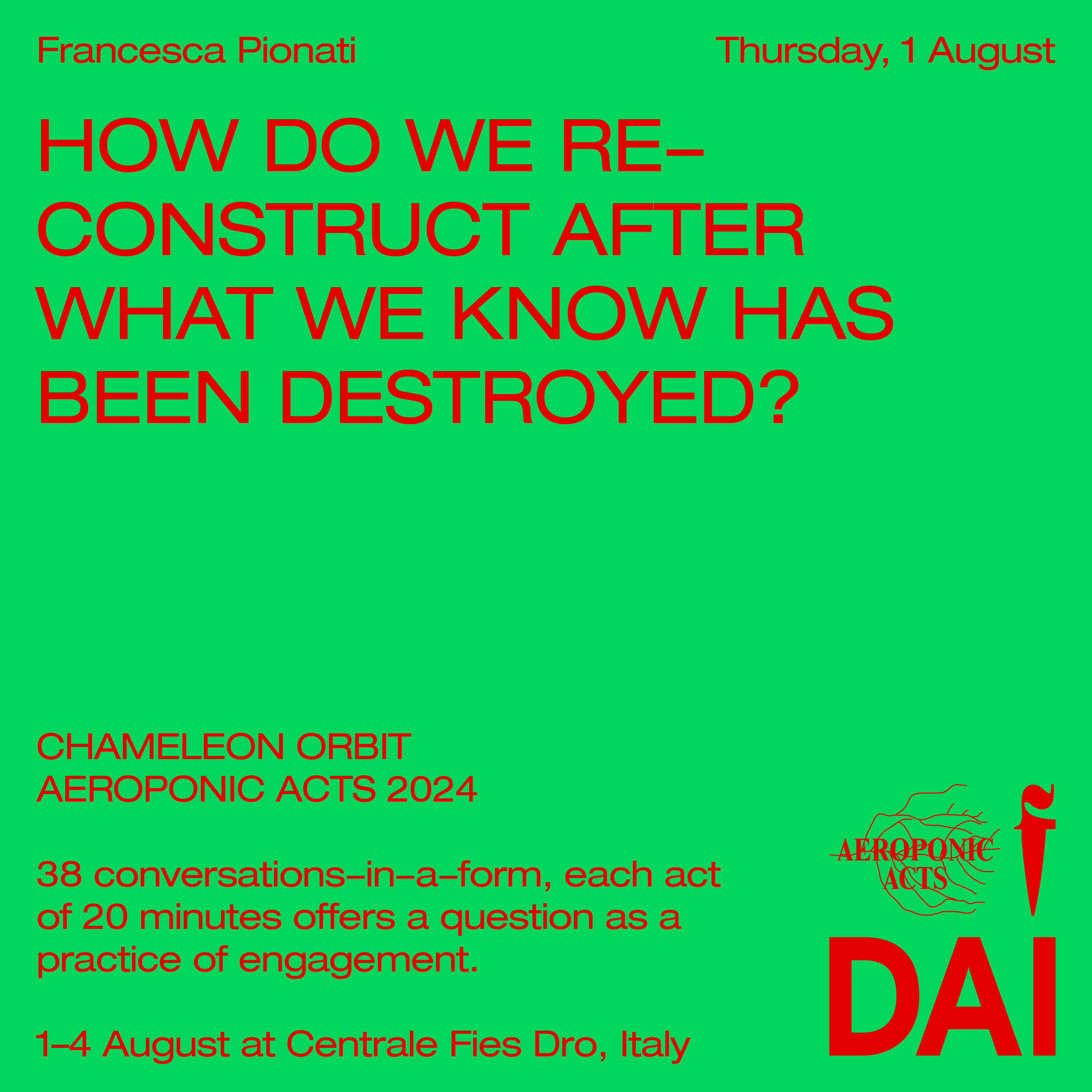

Francesca Pionati ~ FATE PRESTO

1.

When the delegation of Japanese scientists arrived in the destroyed city in Southern Italy for the first time, they could not believe their eyes. No wonder everything came down in the blink of an eye.

But could they really understand what they were witnessing?

2.

Why was the major so obsessed with the reconstruction of the bell tower whose head fell off during the devastating earthquake of 1980? After 10 years of silence, the head was reattached to the body, and the bell started ringing again.

How many still have faith in its sound?

3.

“As Mr. Barra, the lawyer Antonio Barra, who was a very smart person—he must be really old now—said: “You have enclosed the city in the grip of the prefabricated buildings!”

What is more violent, the fall or the reconstruction?

AEROPONIC ACTS 2024 ~ Chameleon Orbit