Evija Kristopane ~ Forget me not

“We looked at him and we knew there was another kind of life: wild, riotous, jolly. He opened a door and showed us paradise. He’d planted it himself, ingenious and thrifty. I don’t believe in model lives, but even now, a quarter century on, I ask myself, what would Derek do?”—Olivia Laing, Introduction to "Modern Nature" by Derek Jarman, 1982

“Paradise is, first of all, a garden. A garden in which everything we need is there for the taking.”—Joe Hollis, 1962

For a tour of the Paradise Greenhouse, enter through the stairs in the courtyard.

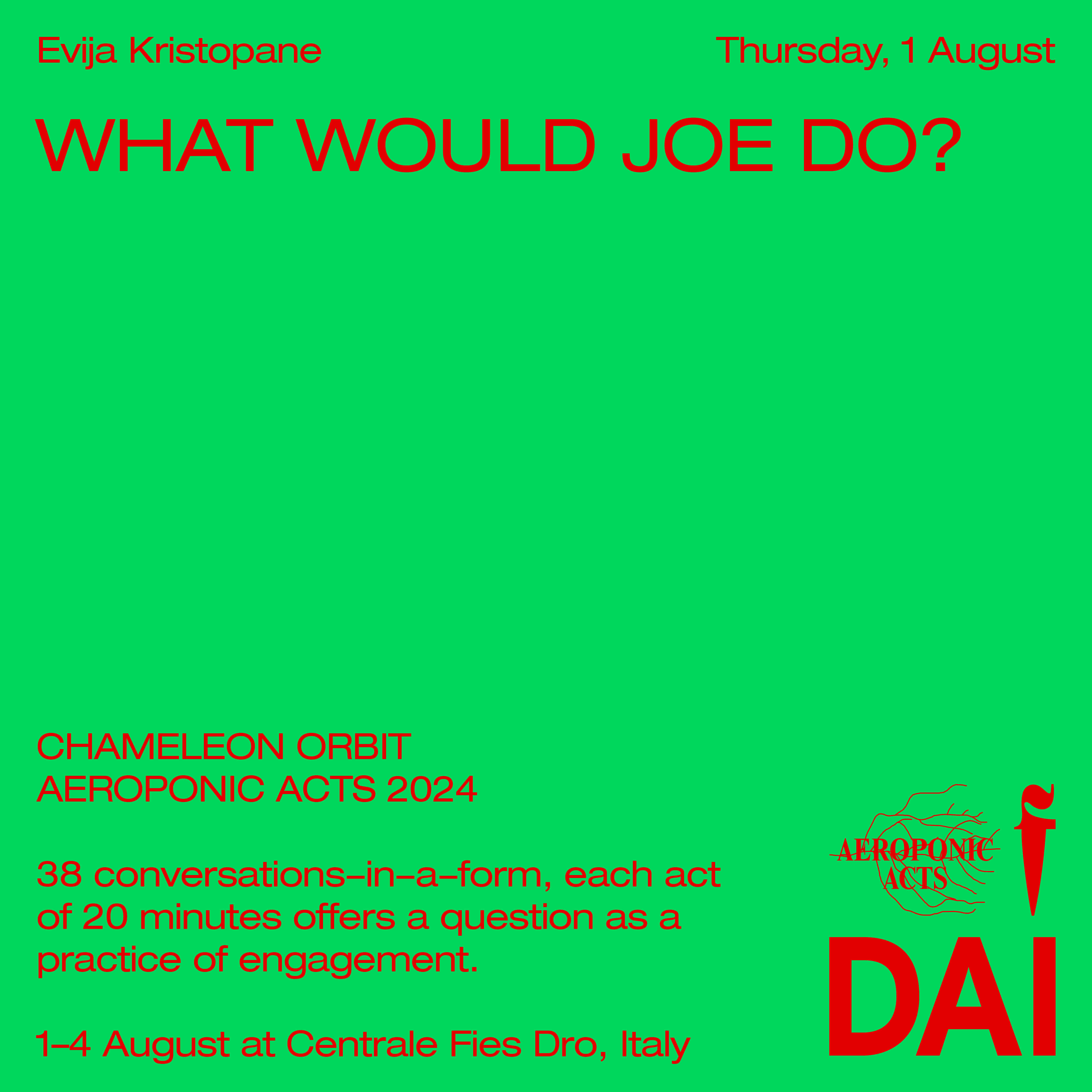

AEROPONIC ACTS 2024 ~ Chameleon Orbit